In 2017, I got a last-minute opportunity to attend BookExpo, a huge annual trade show for the publishing industry. I was new to writing about books and so nervous to be surrounded by Publishing People, but I had a question that I was dying to ask. “What is your next book about fat people?” 2017 doesn’t seem like a long time ago, but the reaction to this question was from a different era. People outright laughed, blushed, or stammered. A few got this panicky look behind their eyes. Some people muttered about Julie Murphy’s groundbreaking YA novel, Dumplin’, which had been out for several years. A few people mentioned Jessamyn Stanley’s Every Body Yoga. Still, in the industry’s largest gathering where the entire goal is to get people excited about upcoming titles, dozens of publishing professionals looked at me, a fat person wearing a press badge, and couldn’t sell me anything.

Slowly, the world has generally begun to realize that fat people are a demographic with money to spend. Representation has spread in the modeling world, and clothing brands are inching towards inclusion. Publishing has taken strides to include fat people (mostly women), especially in the YA and romance categories. Open discussions about body neutrality and dissolving diet culture are less fringe. But it has taken much longer for the representation of all body types to reach the world of picture books.

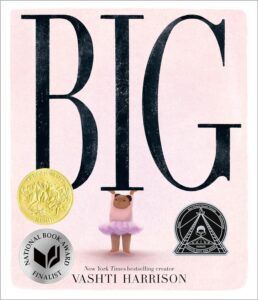

A few summers ago, I wrote about the need for fat kids in picture books. While calls for diversity in children’s publishing have led to more (not enough, but more) books featuring BIPOC children, the concept of including children in fat bodies is moving slower. School nurses and Facebook mom group moderators are grimacing. Do we really want to send children the message that it’s okay to be fat? Short answer: yes. It’s crucial. Thankfully, over the past few years, the tide has been turning. Publishing is catching up. And when Vashti Harrison’s book Big, about a beautiful fat ballerina rejecting negativity from a fatphobic world, won the Caldecott medal in February of this year, I outright cried. When a colleague said they were hesitant to share the book because of the taunting and laughing that would ensue, those tears choked me. This was a wise librarian friend who could navigate tough topics. And there wasn’t a precedent for talking to kids about a book like this.

We can’t just skip it, but we can prepare to face the discomfort head-on. This was my literal first step after reading Big to my students. I asked them to please put a thumb up if they felt uncomfortable while reading this book. I shared that it was uncomfortable for me, too — that reading the teasing from the kids and adults in her life hurt me. We poured over the illustrations and talked about how the main character sorted the descriptors others gave her, choosing to keep the word fat when it was in pink and return it when it was black. We looked for what we thought the girl liked about herself. We focused on the fact that not everyone understood why the girl stood up for herself, but she did, anyway. The conversation after the book was as important as the book itself. I think it is one of the most important books about fat bodies and self-acceptance I’ve ever seen.

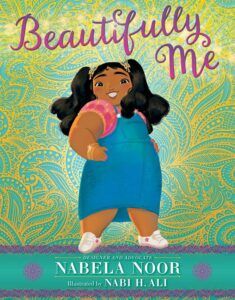

Other books have crept onto the scene, some best suited for the youngest readers and others that I would more likely share with students who can handle an additional ten minutes to talk it through afterward. Our Bodies, written by Kailee Coleman as a companion to her viral song by the same name, is perfect for kids five and under. Let’s get the message out about body variety as early as possible. Nabela Noor’s Beautifully Me, about a Bangladeshi child who struggles with the negative body messages she receives from her family by overhearing their self-talk, needs a more nuanced discussion. The overall message is that kids are listening and absorbing their own body values from us, but a large part of the story is hearing those negative body messages read out loud. With younger kids, I would do some editorial narrating between pages. “Oh, man. I don’t think her sister needs to be smaller to look beautiful! I wonder how Zubi feels when she hears that?” This lays the groundwork for the ending when the adults apologize and agree to be careful about how they talk about bodies.

Not every book about fat kids is built the same, and some have come under criticism that makes me think. Julie Murphy’s Chubby Bunny is about a girl who gets teased for being great at this game. In the story, she ends up owning her teasing and winning over the class. People have pointed out that the kids in the story faced no consequences, and the work had to come from Bunny. Some reviews feel this isn’t the message they want to send to fat or straight-sized kids. This point bears considering! I think this is an area where a good conversation is crucial. Ask the kids what they think! Should those mean taunters have gotten in trouble? If you were the author, what would you do differently?

There are still more fat people than books about them, but I am excited that this is something publishers are considering. I am excited that these are conversations that will continue happening. I am over the moon that Big won its incredibly deserved Caldecott medal, and cannot wait to include this in my picture book units for all of time. We need to read these books and we need to have these conversations. I dream of a world where children don’t crack up when someone says the word “fat.” I think books could get us there.