Book Riot and EveryLibrary have teamed up to execute a series of surveys exploring parental perceptions of libraries, and our first data sets were released at the end of September. These specifically explore the ways parents perceive public libraries. Looking at the results gives a sense of deep tension — 92% feel their children are safe at the public library, and most parents (66%) report not having their child borrow a book that made them uncomfortable. While most parents have no idea how librarians choose the books in the collection (53%), and most also believe librarians should be responsible for collection development and maintenance (58%), one of the most surprising findings was that fully one-quarter of respondents believed librarians should be prosecuted for giving children access to materials.

But what else do these 25% of parents believe about libraries, book banning, and access to materials? I’ve isolated the respondents to the question in order to look at any potential trends among the rest of their responses. First, demographics in both groups are nearly identical when it comes to gender, age, race and ethnicity, and education level. Political affiliation differed a bit, with more of the subset identifying as Republican (37%) than the overall survey (29%), and the percentage of registered voters is identical. The subset had a higher average annual income, with 17% reporting incomes between $100,000-$124,999; the full survey had only 11% report that as their average (the whole survey had a higher percentage in the $25,000-$49,999 category, 21% to the subset’s 16%). Both the original set of parents and the subset use the same social media outlets with similar regularity, except for one instance. The subset is more active on Twitter every week (38%) than the overall survey respondents (31%).

A total of 387 responses were analyzed, all of which responded to the statement “Librarians should be prosecuted for giving children access to certain books” with either “I agree” or “I somewhat agree.” This is more than a quarter of respondents, but exploring the “somewhat” response feels as important as the one that is solidly affirmative. Here’s what these parents stated about other topics across the survey.

Most of those who responded this way had visited a public library in the last 12 months (95%), had an active library card (93%), and fell between being average visitors to the library and frequent visitors. In other words, they report using the library as much as they perceive the average person does, up to using it twice as much as the average person. These are not parents who are unfamiliar with their local public libraries or who do not use them with regularity.

As seen with the overall survey responses, most did not know how librarians selected books for the collection — 68%. Yet, despite not knowing how librarians did the work of choosing materials for the library, this entire slice of survey responses agreed or somewhat agreed with prosecuting librarians for that same material. Indeed, this percentage of respondents being unfamiliar with the processes librarians use for selection is much higher than it is for the survey overall, wherein only 53% were unfamiliar.

People who do not know how librarians select material are much more likely to also believe librarians should be prosecuted for that material. This is chilling, to say the least. It’s also an important point to emphasize for library workers. Where and how do you educate your patrons about the process behind the acquisition of books, movies, and other collection items? If this demographic who somewhat or wholly believes librarians should be prosecuted for materials is your average or above average user, there is a lot of opportunity — maybe even necessity — for education.

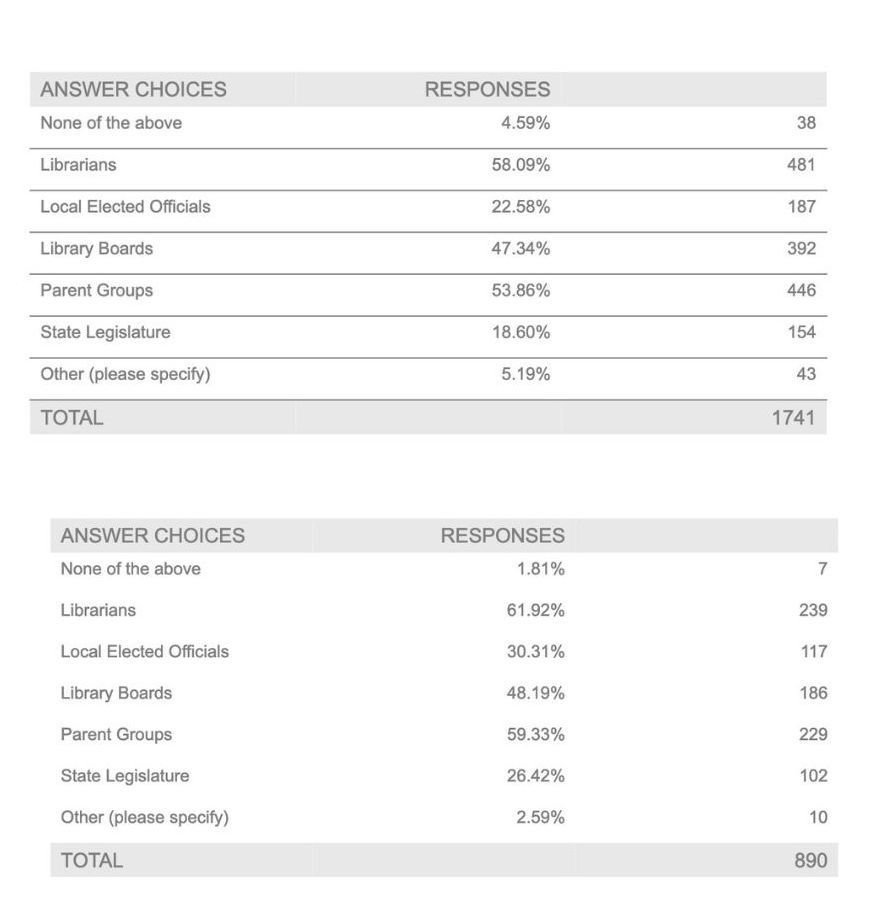

Despite believing that librarians should face prosecution for the materials in the collection and being unfamiliar with how librarians do their job, most of the respondents believe librarians should be the ones making decisions over what the library has. However, the percentage of those who believe parents should have a say in the process is much higher among this segment than it is among the broader survey. 59% voted for parents to be primarily involved in selecting library collection materials, just below the 62% for librarians. They were also much more likely to believe state legislators should be involved in the process than the broader parental population. Here’s a side-by-side, with the responses from the full panel on top and the subset on bottom:

What stands out is the rate at which the subset of respondents put their trust in elected governmental officials. Interestingly, this survey did not articulate the difference between an elected public library board and an appointed public library board.

Among the subset, there was a much higher percentage of parents who reported that their children borrowed materials that made them, the parent, uncomfortable (53%) as compared to the whole (34%). They also reported a higher percentage of children checking out books that made them, the child, uncomfortable, 48% against the whole’s 32%. If the parents in this subset have had these experiences at a higher rate than the whole of the parents taking the survey, then why are they not more familiar with the process of materials acquisition by libraries?

The data on comfort levels related to different themes in books for young readers is consistent across this subset and the larger response. In both, 36% of respondents were not comfortable with LGBTQ+ themes in books for those under 18, roughly 20% in both were not comfortable with children’s books about race and racism, 14% in both were not comfortable with children’s books about social justice, and 23% were uncomfortable with books about sex and puberty.

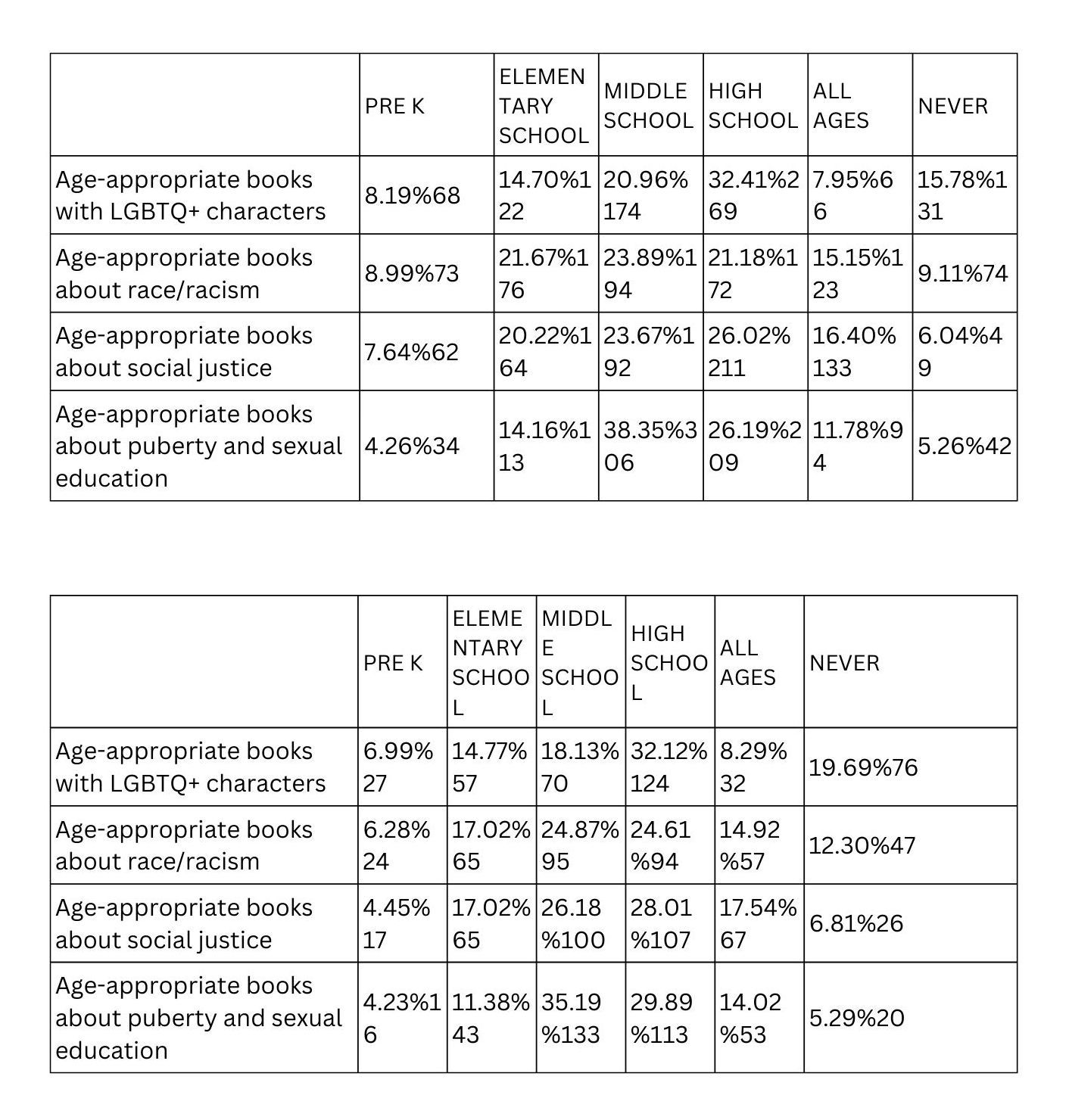

There were, however, stark differences in when the two groups believed access to these books for those under 18 should never be allowed. As before, the top numbers represent the whole survey while the bottom, the subset who say they somewhat or fully believe librarians should be prosecuted for collection materials:

More parents who agree with prosecuting librarians for collections believe people under 18 should never have access to age-appropriate books with LGBTQ+ characters than the broader population, as well as never have access to books about race and racism. Nearly 20% of these parents believe no child should ever have access to age-appropriate books that as much as feature an LGBTQ+ character. Character, not even content.

It will come as no surprise that this subset believes in higher percentages that those same categories of books — age-appropriate titles with LGBTQ+ characters and those about race/racism — have a negative impact on children.

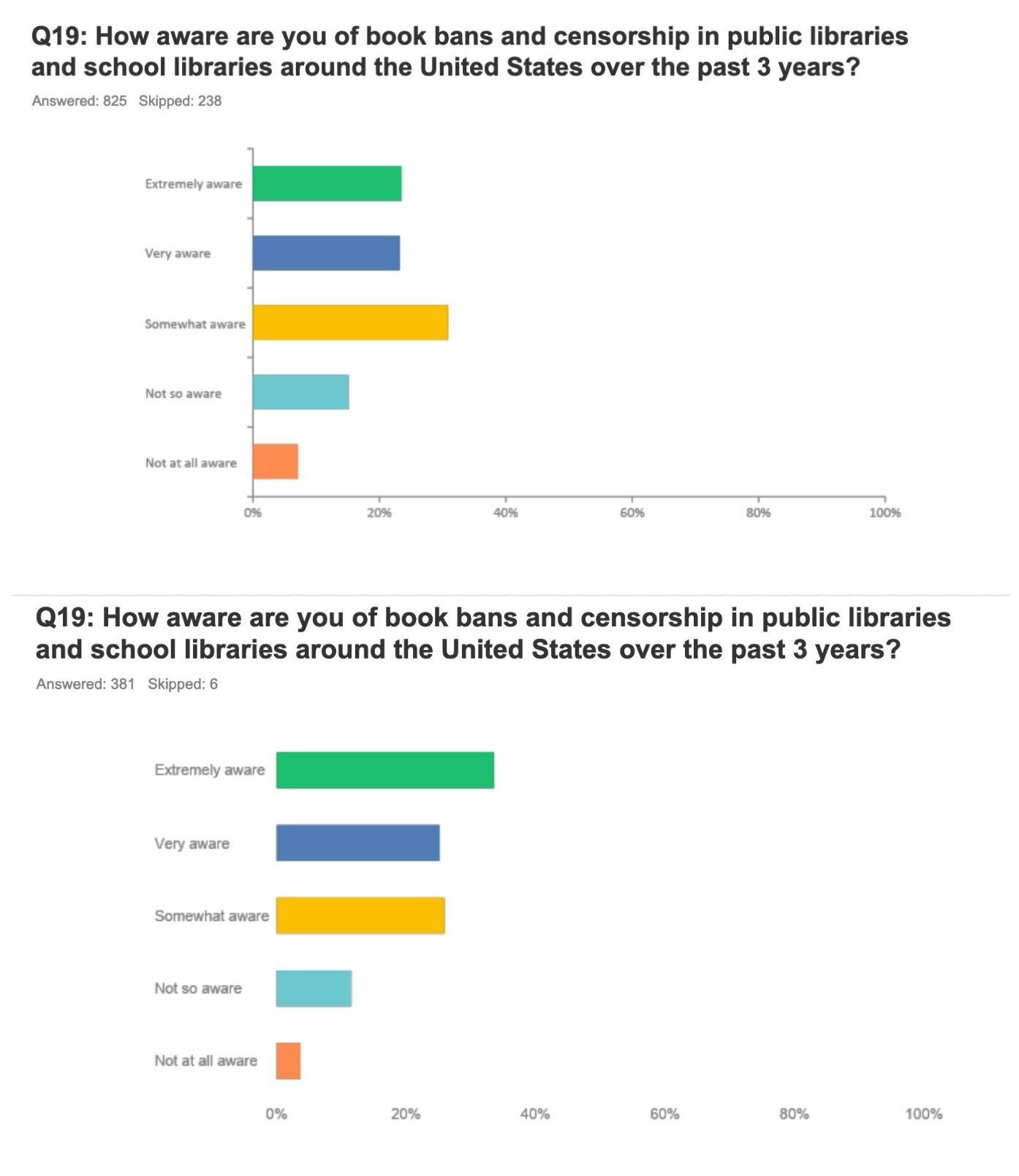

This subset of parents also reports being far more aware of the landscape of book bans across the country right now than the larger data set. While the whole survey of parents showed a spread in their knowledge of book bans, those who believed in prosecuting librarians for the materials in the collection claimed to be very aware of book bans at a much higher rate:

34% of parents who believed in librarian prosecution consider themselves “extremely aware” of censorship and book bans in libraries over the last three years, compared to only 24% in the survey as a whole. The difference in those reporting being “somewhat aware” is wide as well: 26% in the subset to 31% in the whole. Does this suggest that those who are eager to place the blame on librarians are comfortable with that admission because they have been getting their news about library materials from unreliable sources? From sources that are putting targets on the backs of professionals? They are less likely to agree that book bans are a waste of time (34% to 38%), much more likely to say that banning books is the right way to prevent children from seeing something inappropriate (49% — nearly half — compared to 31%), much more likely to say that some books in the children’s section of the public library are inappropriate for all children (46% vs. 31%).

And yet, this same subset does not differ much in their beliefs that banning books infringes on their rights as parents to make decisions about what their children read (39% vs. 42%). In fact, the subset was more likely to state they are responsible for what their child reads (62% vs. 58%) and that parents should be involved in helping their child decide what to read (70% vs. 67%). It is okay to ban books because it is the right way to prevent children from seeing something inappropriate, but it is also an infringement on their rights to decide what their children have access to. These parents have had more experiences with books that have made them or their child uncomfortable, but they also claim with more frequency that it is their job as parents to help their child choose what to read.

These responses are confusing to hold and consider simultaneously.

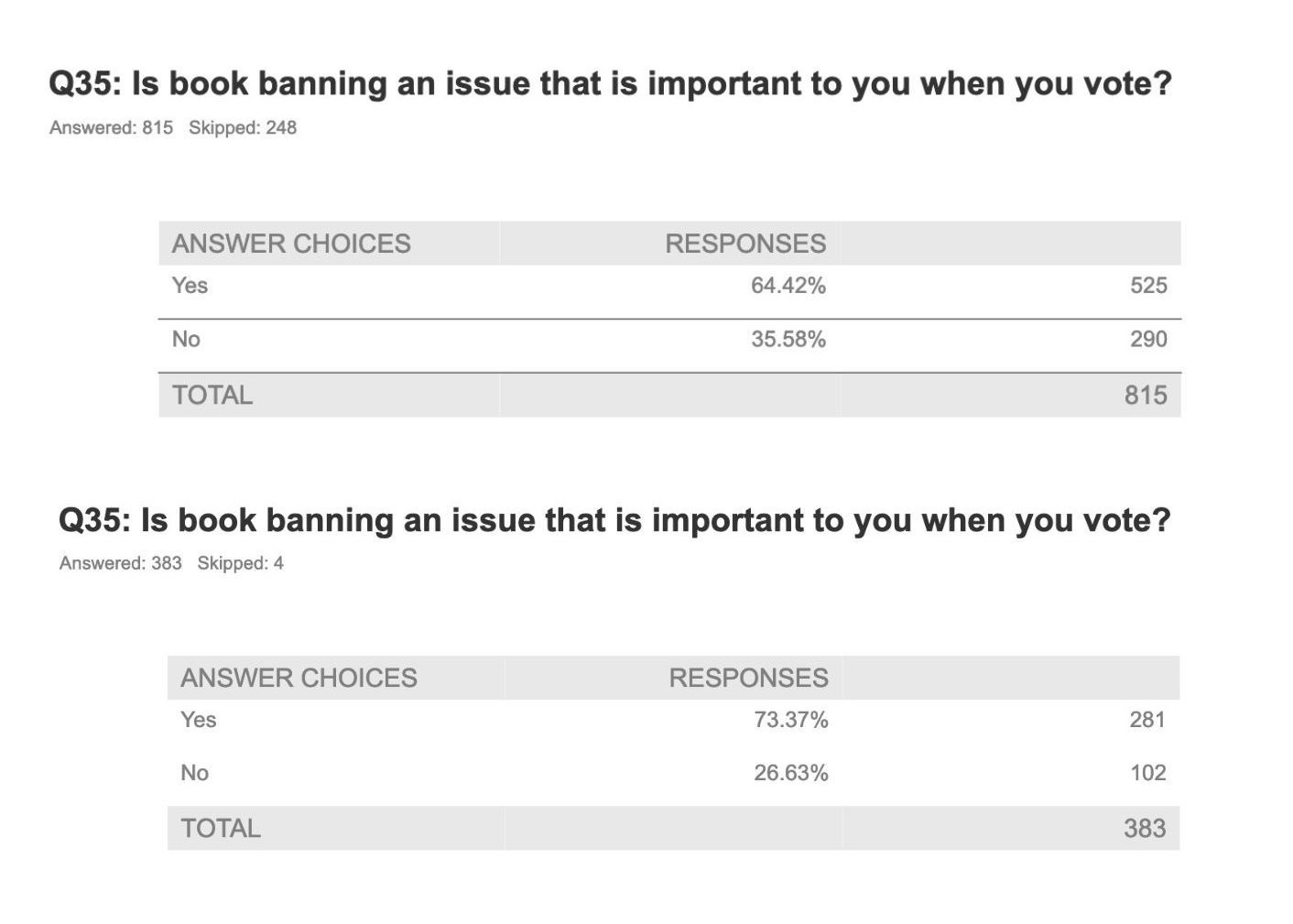

It should be concerning, too, that this subset which believes in parental rights (except for their own over their children) and who believe in prosecuting librarians for materials in the collection (even though they don’t know how materials are selected) are more likely to consider book banning an important issue to them when they vote.

It is hard to understand what any of this means in isolation, let alone what it means, taken as a whole. It appears that some of the talking points spewed by right-wing media are sticking with the average parent, including rhetoric that librarians are attempting to indoctrinate or groom children. This thread runs through the notion that there is never an age when people under 18 should have access to books with LGBTQ+ characters and the disparate responses to the level of discomfort parents have felt with books borrowed by their children and their belief that they get to decide what their children read.

Not to mention that 25% of parents believe in prosecuting librarians for the materials on shelves.

There is much more to be explored in the data, and those deep dives will continue through the next several weeks and months as the results of the next pair of surveys emerge.

Book Censorship News: October 12, 2023

Erica and Danika adapted the last couple of weeks’ worth of book censorship news roundups and did a tremendous job. In the interests and needs of time, I will not be retreading the stories that were published in those two weeks. Find below a roundup beginning with news on Friday, October 4, and forward.

- This week’s news includes several library directors who have been ousted or quit because of being asked to remove queer books. Starting in Suffield, Connecticut’s public library: “‘I have been instructed to run the library in ways that conflict with my professional ethics, experience, and training. So, it is time for me to move on,’ Styles said, adding that town officials directed library staff to remove certain books based on certain topics, in her opinion sending a message that some people who the books represent are not important.”

- 23 books were removed from Spotsylvania schools (VA) this week. Recall one of their board members called for burning books last year; that individual is chair of the board now.

- In Seminole County Schools (FL), 31 books were pulled…because they’ve been pulled at other Florida schools.

- Parents who care about the right of students to read books and the bigots who don’t showed up at Cherry Creek schools (CO) this week. Here’s a rundown of that story, and it’s worth highlighting that this school got a bomb threat from That Twitter Account, naturally. The problem is not the books. It’s right-wingers.

- In Saline County, Arkansas, where the county judge took over control of the public library, the library’s executive director has been “let go.”

- There is a supervisor in Marathon County, Wisconsin, who is proposing killing the budget of the county library system over a few books that the library won’t ban. America, 2023.

- Because Pella Public Library (IA) did not remove Gender Queer from its shelves, the city wants to revoke the power that the library board has in overseeing the library. This is fascism, just like the story above. The issue will be on the ballot for the community, which is a reminder that if you have local issues, you need to show up and vote on them. I hope that this story has a good resolution, but given how we’ve seen other similar ballot measures not go well — see Patmos Library in Michigan.

- The South Carolina State Superintendent wants to be the one who decides what books can and cannot enter schools and libraries.

- Alabama’s governor wants to tie funding of public libraries and school libraries to policies that would restrict access to books. In other words, this is a policy that would do the precise opposite of what Illinois is doing with its book ban bill. So we’re going to become a country of two tiers of access by law.

- “It’s in response to this national trend that the Wood County library [WV] is changing their Collection Development Policy, which includes the procedure for challenging books and other materials in the library collection. As of Sept. 19, the library requires all challenges to come from active library card holders. Challenges are limited to two titles at a time, submitted separately. The library will also make an announcement when titles are challenged to enable public input.” This is what is going to need to happen on a nationwide scale: allow book challenges, as that is a First Amendment Right.

- Even though all of the book banners claim they are not targeting LGBTQ+ books, it was an author whose last name was Gay who saw a book banned in Alabama. Curious!

- At the Ida Rupp Public Library (OH), there’s a fresh crop of “Clean Up” folks itching to get rid of queer books.

- A Colorado court just ruled that library reconsideration request forms, if FOIAd, cannot include information about the people or groups behind them. That means you might never know the bigots hiding behind their book looks “reviews” to complain about “children’s porn” at the public library.

- DaVinci Academy, a Minnesota charter school, is facing pushback from some of its Muslim parents over the use of LGBTQ+ books in the school.

- Plano Independent School District (TX) believes the nonsense rhetoric around sexually explicit books in their libraries, so they’re revising their policies now. How many books will suddenly disappear?

- A Court of Thorns and Roses will remain in Catawba County high school libraries (NC), though the district will be banning A Court of Mist and Fury.

- “It was a boisterous meeting Monday night for the Burke County Board of Education after dozens of people were bussed to the meeting to ask the board to remove some books from school libraries.” They bussed people in to complain about books!!! This is in North Carolina, and you’ll be absolutely shocked to hear the books they were mad at are all ones that the internet and their fascist Moms leaders told them to be mad about.

- Several books in Bonny Eagle School District (ME) are being reviewed, and at least one high school principal in the district has taken advantage of this and removed several titles.

- The ACLU condemns the Yorkville School Board (IL) for removing Just Mercy from classrooms. This story has involved students demanding their voices be heard, but the board does not care.

- The mayor of Daytona Beach (FL) is concerned a book fair about banned books in the area is going to include banned books. We’re banning banned books book fairs.

- I am paywalled from this story, but it’s a look at the possibility that Pennridge Schools (PA) are quietly banning books. (Naturally, it’s behind an effing paywall).

- Meanwhile, in Central Bucks (PA), two LGBTQ+ books were removed from schools. Not because they’re “pornographic,” but because they “violate policy.” Sure, Jan.

- At Ward Melville High School (NY), the crisis actors are mad about the juniors at the school — 16 and 17-year-olds who are also learning how to drive and can sign up to be recruited by the military during lunchtime — reading Sherman Alexie’s Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

- A *former* teacher in Michigan posted a TikTok about banned books, and a school she has not worked at since 2021 started to get threats because of That Twitter Account Who Loves Stochastic Terrorism.

- (Paywalled) We might finally see a resolution in the months-long debate over a couple of sex ed books at Caro Area Public Library (MI). It appears as though the books will remain exactly where they belong.

- The Moms for Liberty chapter of Northern Kentucky showed up at the state library association to protest…the president of the American Library Association for being a lesbian Marxist. Same boring, tired talking points.

- “Citizens of a northwest Virginia town will continue to have a beloved library after elected leaders voted to fund the institution after months of debate around access to books came to an end. The long-standing discord surrounding including LGBTQ-related books at Samuels Public Library reached a resolution on Tuesday as Warren County officials and library leaders signed a collaborative agreement.” This is GOOD news.

- This will be the great rise of hearing stories coming from the Great Falls Public Library (MT). If the anti-library levy, anti-LGBTQ book candidate is appointed to the board, it’s to push forward in defunding the institution.

- From the photo caption, without the photo, I want you to guess what the person looks like: “Retired teacher Shirley Redford of Newport speaks in support of the Parents’ Bill of Rights recently adopted by the NC General Assembly and encourages Board of Education members and administrators to ensure age-appropriate books are used in county public schools and media centers.” If your guess was older, white, and wearing a bedazzled “USA” bracelet, then you know all you need to on this story (NC).

- Visalia Unified School District (CA) will be keeping 13 challenged books in the schools.

- “The Alta-Aurelia School District [IA] relocated all books for ninth through twelfth grade into classrooms to comply with the legislature’s restrictions on reading materials in schools. No high school students go into the shared library with the city of Alta. The district and the Alta Library have separated the two entities collection preventing elementary students from accessing banned content. Pre-K through fourth grade materials are still in the library and are accessible to students. The city’s collection is partitioned off to the school but open to the public.” This is the future the book banners are hot for — completely cut-off access to books for kids. The details in this story are particularly heart-wrenching, as this is one of the public libraries that serves as the school library, too.

- Can rich people stop sending books to Florida and think it’s a solution to what is an effort to legislate hate? Because that money is better spent getting work done in legislature, not making a website and getting nice press for sending books to kids. We’ve been in this for three years now.

- On the rise of book bans in Minnesota.

- “Faith affiliated groups have employed citizens to read excerpts from ‘sexually explicit books’ at this week’s St. Tammany Parish School Board meeting [LA], shifting book restriction efforts from the parish’s public library scene to its public school district.” This is what they do for fun.

- Two more books are being challenged in Wilson County, Tennessee, schools.

- Berkeley County School District (SC) began their review of the 93 books challenged by one single person. Of the first batch of books, four will stay in all district libraries, and three will remain at the high school only. I seem not to be finding 1. what those books are and 2. information on the other three books reviewed in this session.

- This is a powerful read about how one English teacher in Grapevine Independent School District (TX) became the target of a Christian mother’s ire over gender and her trans daughter. (It’s books, y’all).

Also In This Story Stream

-

74% of Parents Think Book Bans Infringe on Their Parental Rights: Book Censorship News, September 29, 2023 -

Student Groups Against Book Bans: Book Censorship News, September 22, 2023 -

Book Fairs Will See An Increase In Censorship Attempts This Year: Book Censorship News, September 15, 2023 -

Championing Inclusivity in Library Collection Policies: Book Censorship News, September 8, 2023 -

How To Alert Your School Board to Right-Wing Bad Actors: Book Censorship News, September 1, 2023 -

Library Bomb Threats Continue to Increase: Book Censorship News, August 25, 2023 -

Districts Are Turning to AI to Ban Books: Book Censorship News, August 18, 2023 -

Age-Restricted Library Cards Aren’t a Solution. They’re a Liability: Book Censorship News, July 28, 2023 -

How To Own A News Cycle: Book Censorship News, July 21, 2023