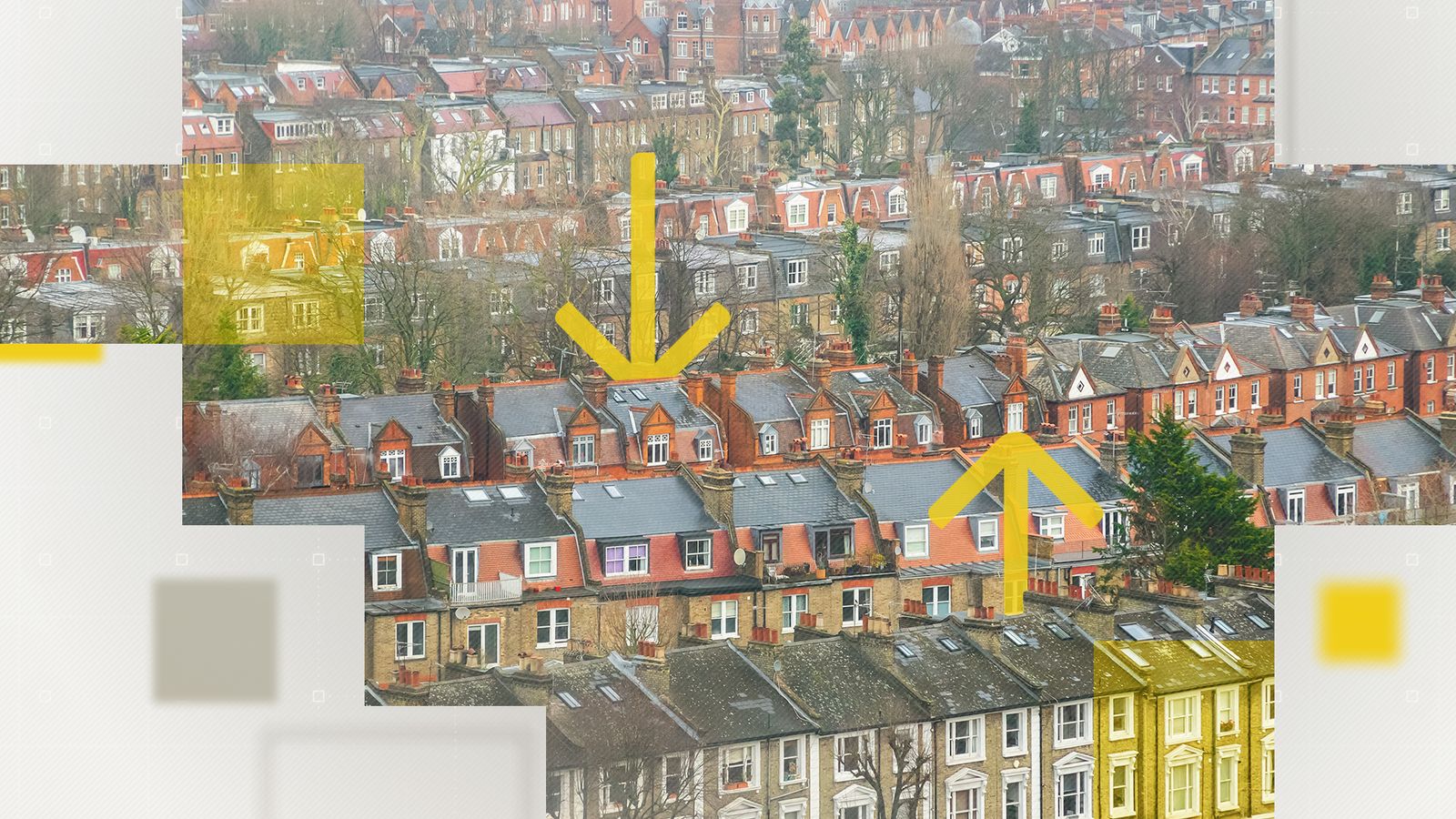

House building has not kept up with population growth in almost half of the local authorities in England, Sky News analysis has found.

In the decade to 2021, the population grew faster or at the same pace as the number of homes in 150 out of 309 local authorities, according to our analysis of data from the recently released 2021 Census and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities.

Experts in the housing sector say we are not building enough even where the number of new properties has kept up with population growth because there were already too few homes.

The number of dwellings in England grew 8.4% over the last decade, while the population grew 6.6%. But this is an average and averages hide the disparities between places.

When there are not enough empty properties, prices are higher and renting conditions are often worse.

Valentine Quinio, senior analyst at the Centre for Cities, says that we need vacant homes to allow the housing market to function properly.

“With very few empty homes, landlords have the negotiation power to pull up rents because they know that renters have no other option,” she says.

In England, only 1% of residential properties are vacant, which is far lower than most European countries.

In Germany, the latest OECD data shows that 8.2% of total dwellings are vacant, while in Japan it’s 13.6%.

The proportion of long-term vacant dwellings in England has not changed much since 2011 and is below 3% in every local authority.

Quinio says the lack of empty properties means more people have to live in house shares.

Our analysis also shows that households are growing in size in the same places where not enough homes were built over the past decade.

“The housing shortage was very much an issue in many cities already, and these are the same cities that are struggling now,” says Quinio.

A lack of supply also means the average quality of the housing stock is lower, as new builds tend to be better insulated.

On average, more than eight in 10 of new residential properties created in England in 2021 were new build dwellings.

But new builds made up less than half of new homes in eight of the 309 areas we analysed, including Portsmouth, Richmondshire and Eastbourne.

What does this mean for house prices?

Prices have increased everywhere over a decade, but the rise has been over 50% in two-thirds of England’s local authorities.

The cost of buying a property has doubled in some London boroughs like Waltham Forest, Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, and Lewisham.

Our analysis shows that prices have increased the most in areas where the population has grown faster than the number of dwellings and in areas where the proportion of empty homes is lower.

Tom Bill, head of UK residential research at real estate consultancy Knight Frank, says there’s often localised shortfalls in housing because “it’s not a perfect system” and properties don’t always get built where they are needed most.

“House builders face red tape, they face uncertainty over government support initiatives like Help to Buy,” he says.

“Often it’s not as straightforward as going in and plugging a hole in supply.”

A dysfunctional housing market has a knock-on effect for population growth and economic development in cities.

Quinio says that, aside from London, major cities have average population growth – a sign that they are “punching below their weight” when it comes to house building.

“They should be above average because they should be driving economic growth,” she says. “[A shortage of housing] is essentially stunting household formation.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities said: “Comparing population growth with new houses built does not take into account those who live together.

“A more meaningful analysis is to compare the number of households – between 2011-21 there were 1.9 million additional homes in England, while the number of households increased by 1.37 million

“We remain committed to reaching our target of delivering 300,000 homes a year and just before the pandemic struck housebuilding reached the highest level in 30 years – with over 242,000 new homes built.

“We’re investing £11.5bn to provide up to 180,000 affordable homes across the country, alongside a £1.8bn investment to support the regeneration of brownfield land, delivering more local housing, transport and better infrastructure for local communities.”

Methodology

Local authorities are based on 2021 boundaries. For those authorities whose boundaries changed between 2011 and 2021, we have tracked and matched the previous boundaries. Areas affected are: Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole, Dorset, Buckinghamshire, West Suffolk, East Suffolk, Somerset and Taunton, West Northamptonshire and North Northamptonshire.

An area is considered to have a non-healthy housing market when the difference between the growth of the population and the growth of the number of dwellings in stock is greater than -2 percentage points. Years refer to financial years.

Vacancy rates refer to long-term vacant properties only, which includes dwellings that have been empty for six months or longer. This does not include dwellings registered as second homes.

The Data and Forensics team is a multi-skilled unit dedicated to providing transparent journalism from Sky News. We gather, analyse and visualise data to tell data-driven stories. We combine traditional reporting skills with advanced analysis of satellite images, social media and other open source information. Through multimedia storytelling we aim to better explain the world while also showing how our journalism is done.

Why data journalism matters to Sky News