It’s February of 1828. The Cherokee Nation, which spreads across several southern states, is being pressured by the United States government to either move west of the Mississippi River or to end their tribal government and cede their treaty rights to the United States. In the Nation’s capital of New Echota (located in present-day Georgia), a group has come together to try to develop a news source for and by members of the Cherokee, one that will advance Native voices and provide information in both the Cherokee and English languages.

Galagina Oowatie, who adopted the English name Elias Boudinot, was born in 1804 at Oothcalooga, Cherokee Nation. As a young man, he learned both Cherokee and English and attended the Foreign Mission School, an institution dedicated to training missionaries, in Connecticut. There, he met and married Harriet R. Gold, a Congregationalist and the daughter of prominent figures in the Cornwall, Connecticut community. Harriet and Elias’s marriage was the second prominent Cherokee-white marriage in the Cornwall community, and Harriet faced strong opposition from her parents and her church community. Perhaps partially because of this treatment, the couple moved soon after their marriage to New Echota, where Elias owned a house.

Elias was far from the only member of New Echota to have missionary training, though he was unique in being a member of the Nation as opposed to an outsider. A fellow missionary, Samuel Worcester, had become a close friend of Boudinot, and it was through their joint work that the idea for a Cherokee Nation newspaper was developed. Another member of the Nation, Sequoyah, had developed a syllabary for the Cherokee language, making it possible for the first time to write in Cherokee. Part of Sequoyah’s inspiration for the creation of his syllabary was the hope that it could be used to print news like that in the English-language papers he had seen.

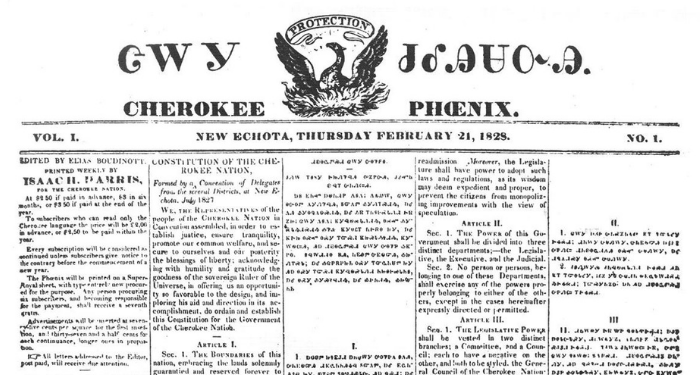

Boudinot, seeing the need for a way to disseminate news across the larger Cherokee Nation, reached out to his friend and fellow missionary, Worcester. Worcester had experience in printing, as a large part of his missionary work had focused on printing the Bible in Native languages, including the newly written language of the Cherokee Nation. With Worcester’s equipment and Boudinot’s family connections in the Nation, the two of them launched the Cherokee Phoenix in 1828, with five columns spread across four pages.

Due to the time commitment of translating the columns written in English into Cherokee, only three columns were translated in the first issue. Topics covered in this first printing included a story from Worcester praising Sequoyah for his work on the syllabary, and an editorial from Boudinot speaking against settlers trying to take Cherokee land. Before long, the paper became the main vehicle of national communication between the townships that made up the Cherokee Nation, an area that stretched through present-day Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina. As the issue of potential Cherokee removal to the west gained more attention, the paper was also used to generate support and to fundraise in support of the Cherokee Nation. In order to drum up this interest, Boudinot gradually moved toward publishing mostly in English, and subscribers came in from both around the U.S. and throughout Europe.

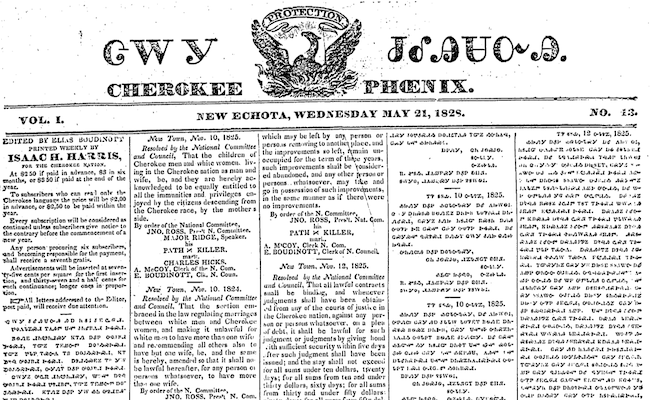

In 1829 Boudinot renamed the paper the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate, reflecting his belief that he was addressing issues of concern to the larger Native American population. The paper covered issues related to removal, including Supreme Court cases that would affect Native rights. At the same time, conflict was brewing within the Cherokee Nation. As the U.S. government continued to pressure the Cherokee to give up their land, the Nation became split between those who favored negotiating a settlement with the United States and those who wanted to resist any type of removal or new treaty.

Boudinot, unlike most members of the Nation, supported negotiation, a position in which he was backed by Major Ridge, a Cherokee leader who had been an early supporter of the paper. Challenging this view were John Ross, the Cherokee Nation Principal Chief, and his supporters. Ross was angry that Boudinot, as editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, continued to support negotiations with European Americans and that he voiced this support through his publication. In 1832 Ross, in his role as Principal Chief, forbade Boudinot from publishing pieces that supported treaty reconciliation and Boudinot resigned in protest. He was replaced with Elijah Hicks, an anti-removal Cherokee, and Ross’s brother-in-law.

After Boudinot’s departure (and eventual assassination in 1839), the paper limped along before ceasing publishing in 1843 when the United States stopped paying an annuity to the Cherokee Nation. In an attempt to silence Ross, Hicks, and other anti-removal Cherokee voices, the Georgia Guard destroyed the paper’s printing presses and soon the U.S. enacted its policy of removal, sending the Cherokee into Indian Territory via the Trail of Tears after seizing their land.

While Boudinot was no longer editor, Samuel Worcester, who had protested the taking of Cherokee land, continued to promote its publication. Worcester left with the Cherokee who were sent to Indian Territory and brought the first printing press to the area. The Cherokee Phoenix continued to publish sporadically throughout this time, and today these printings can be viewed in the collections of the University of Georgia.

When he first conceived of the idea to publish his paper, Boudinot had chosen its name for the connotation of rising out of a troubled time. In the late 20th and early 21st century the Cherokee Phoenix rose again, this time as a monthly broadsheet published by the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, as well as online. Today, it endures as both a modern news source and a legacy of the first, and now the most enduring, Native language paper in the United States.